Buthayna Ali, We Nous نحن, Installation, 2006

From outsized sling shots to gently illuminated swings, Buthayna Ali has become knownfor her immersive installations, inviting the viewer to physically step into the space, become surrounded by the various elements on display, and become a part of the sensory environment. A professor at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Damascus (where she has lectured for over 20 years), and with work in international collections including Mathaf: Arab Museum of Arab Art and the Khalid Shoman Foundation, Darat Al-Funun in Amman, it might surprise some to know that the career of this innovative installation artist actually began in the far tamer realms of painting. This, she explains. was largely due to the focus on traditional art-making methods at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Damascus at the time (the mid 1990s), after which she moved to Paris, where she gained her diploma in painting from the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. “During my studies, I was introduced to the new world of art of the 20th century, and discovered that there are no limits in art,” she explains. “Years after, I started to feel that my ideas could be conveyed on canvas only. I wanted something else – I didn’t want to feel limited to traditional materials or methods. I wanted to be able to utilise any material I needed in to express and visualise my concepts.”

Buthayna Ali, Tent, Installation, 2001

This realisation led to the creation of her first installation, My Tent, in 2001, which presented the titular tent divided into two parts – one signifying the harsh realities of the desert, and the other the warm colours with which Bedouins decorate their lives. The installation was accompanied by a soundtrack of Bedouin instruments. This amalgamation of different elements (be they painting, sculpture, sound or space) marked what she refers to as “my first step into the world of installation art – a world in which viewers could physically enter the artwork and interact with it using all of their senses.” For Ali, this was the turning point. “Immediately, I knew this was what I wanted: for my work to be an experiment and an experience, and to be able, through my work, to shape different forms using any element, any medium, as long as they serve that experience and serve the work.”

Buthayna Ali, We Nous نحن, Installation, 2006

One of Buthayna Ali’s best-known installation works is probably the 2006 We, in which a series of children’s swings hang suspended in a room. Spotlights illuminate each, highlighting words drawn from a survey the artist took in which she asked people what, for them, represented the meaning of life. These lights then outline the shape of each swing against the floor. “After returning from France to Syria in 2001, the Intifada started in Gaza, followed by the Iraq War just two years later,” she says. “I was severely infected by the disturbing footage I saw in the media.” The effect of these scenes resulted in Promises, a 2003 installation including burned out elements and barbed wire. Another two years passed, and Ali felt ever more strongly the need to “disconnect from all the chaotic wards and political plans, and reconnect with my peaceful memories and childhood innocence. I failed.” The result – We – was based on a children’s game, but metamorphosed into one for adults.

In more recent years, the ongoing conflict in Syria has seen Ali halt her artistic production for the time being, although she continues to teach. “I’ve stopped working [on my own art] for many reasons,” she explains. “The most pressing is the fact that I am actually in the thick of this all – I simply can’t see anything else. Being in a war is nothing like watching it – it’s so difficult. I have so many ideas, but right now, the focus has simply been on staying alive with my family and students.” As a teacher, Ali focuses on the foundations of drawing and painting before allowing her students to experiment with tools and ideas. “I love helping my students improve and develop their work,” she says, “and, ultimately, being in touch with the new generation of artists keeps me updated in so many different fields.”

Here, Buthayna Ali talks us through some of her most significant works.

Buthayna Ali, Y...Why, Installation, 2010

Y... Why (2010)

When I moved to Canada in 2008, and while I was working on the installation Examples [comprising 30 photomontages], I was constantly asking myself: why am I here? Why I did I leave my homeland? Why do people choose to emigrate? The answers to these questions were sketches of slingshots… shooting us to other places, playful yet dangerous. When the curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath of Art Reoriented contacted me the following year to be part of the exhibition Told Untold Retold at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, I presented the idea, which then became a reality and became this installation of slingshots. Emigration and immigration have always been big questions to me, which in turn have led to an even larger question: what is the meaning of ‘homeland’?

Buthayna Ali, Don't Listen! She's Only a Woman!, Installation, 2010

Don't Listen! She's Only a Woman! (2010)

The installation featured two large steel lockers placed in a hammam. They were both the same size (120 cm W, 40 cm D, 210 cm H), and each was five tiers high and three units wide. Inside each unit there were bags containing personal items belonging to different women – similar to what one can find in a female gym locker. Without a doubt, the contents of a woman’s bag (or, in this case, locker) can say a lot about who she is. There was also a sound element in this installation. Each locker included an MP3 player which had recorded on it a woman’s voice speaking about her daily problems, and talking about her life in general, concerning mainly the men in her social circle. I chose women from different countries, with different backgrounds… so in total there were 30 bags and 30 MP3 players for 30 women. When the unit is closed, the viewer can hear the sound and a light is on, and when the viewer opens the unit, the sound and light turn off.

Buthayna Ali, No Comment, Installation, 2009

No Comment (2009)

This installation comprised a transparent Plexiglas box inside which I placed three holy books: the Qur’an (Arabic), the Bible (Aramaic), and the Tanakh (Hebrew). The viewer was also able to hear religious songs and hymns from the three faiths, all playing simultaneously, with one getting a little louder at times to overpower the other two.

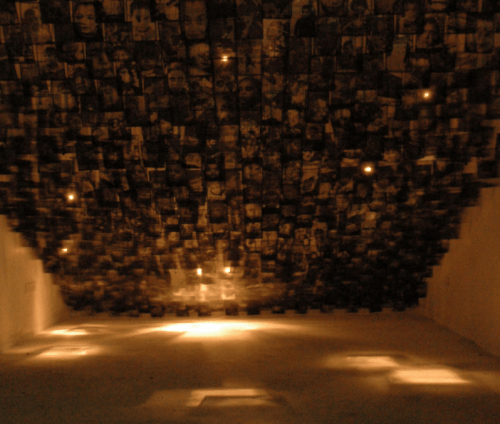

Buthayna Ali, I'm Ashamed, Installation, 2009

I'm Ashamed (2009)

Setting up this work was both a delicate and a complicated process. It was installed within a room in Dubai’s old town of Bastakiya, in a rectangle-shaped space measuring 355 × 843 x 323 cm. I’m Ashamed featured 700 photographs of children in Gaza (collected online during the war – a challenge in itself), printed on transparent sheets. These pictures then hung consecutively in rows from the ceiling, each suspended on four transparent strings. Spotlights were installed behind the pictures, which shone through and projected their content onto the floor. Viewers were able to walk underneath some parts of the installation, listening to the sound of strong wind.

Buthayna Ali, Ayn, Installation, 2008

Ayn (2008)

In this video installation, circular screens reflected the shape of Sufi whirling dervishes in a symbolic imitation of the way the planets of our solar system orbit the sun. The dancers were filmed from above, effectively giving the viewer a birds eye view. The Sufi dance is a physical act of meditation which aims to reach and connect with God (in the sky), by completely disconnecting from the materialist world around us. However, in addition to the meditative music (called Ayn, after which the piece takes its name), the viewer hears glitches – noises and sounds as well as the voices of the dervishes talking about their lives and describing their daily struggles. There are visual ‘glitches’ as well – lines of videos of the busy downtown streets of cities, traffic and people – all symbolising the challenges faced when trying to achieve complete serenity. The screen on the floor was designed to reflect the end of the dervish’s dance, and to symbolise his return back to earth.